In Denis Villeneuve's "Dune" film and the 2003 "Children of Dune" series, we witness two versions of the base castles on Arrakis, with their prototypes tracing back to the pyramids—considered the closest real-world example to the concept of megastructures. We need to use them to understand the relationship between megastructures and "power": How are megastructures produced under the mechanisms of power? And how do megastructures represent and symbolize power?

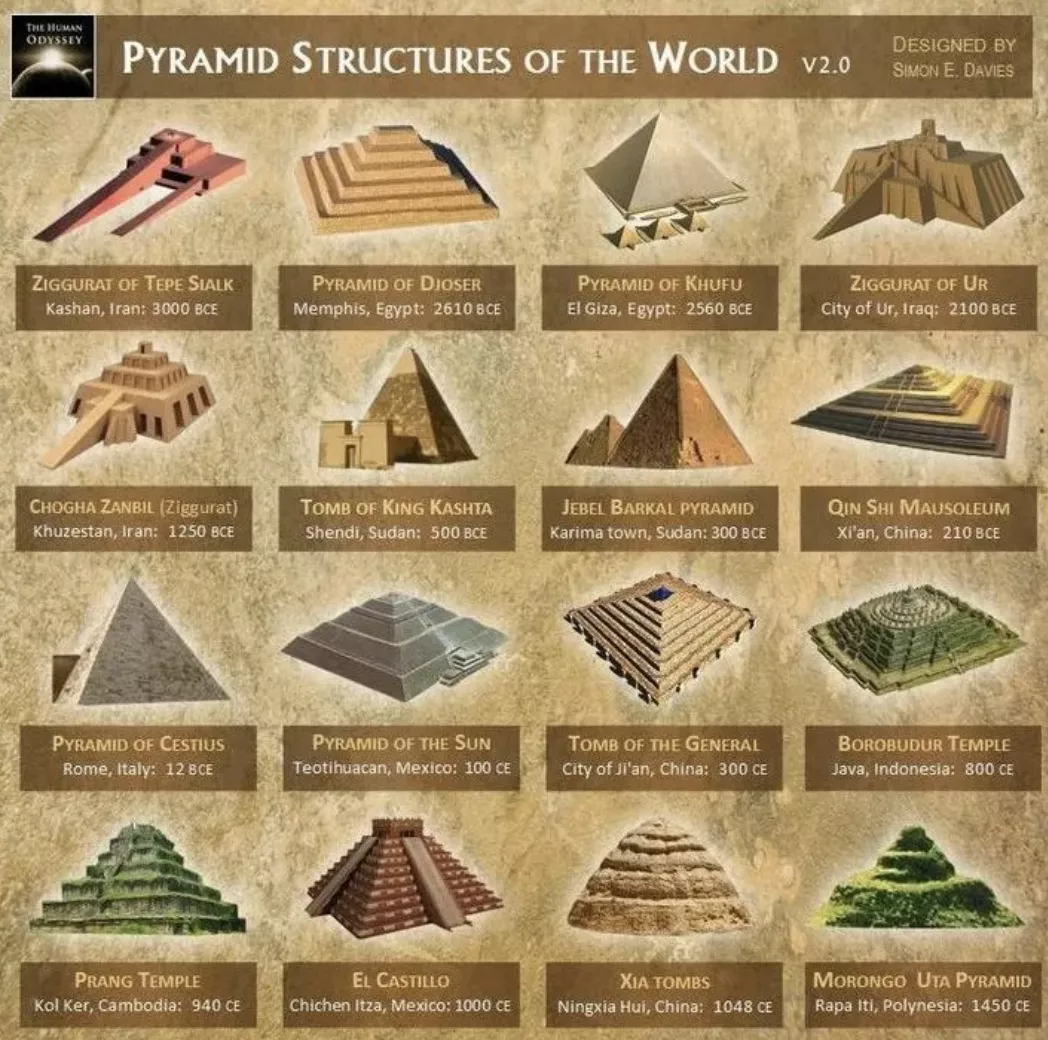

The pyramid is the pharaoh's tomb, unless one day it's proven to be an artifact of some extraterrestrial civilization. I prefer to believe it was built through the forced labor and conscription of workers—dependent on human labor production, it's a human creation. Standing at the foot of the pyramid, the direct contrast between its enormity and human insignificance isn't merely "BDO-style"; it's not devoid of thought. Amidst the awe, we seek an explanation: For those who built it, this awe comes from the labor itself, reliant on vast manpower under backward production conditions, and the control over this massive workforce—the energy of power.

Because the pyramid's construction was "All for one," driven by power to exploit manpower (by whatever means), it also represents and symbolizes it. Hence, our emotions toward the pyramid are extremely contradictory. On one hand, we marvel at it as evidence of the heights human civilization has reached. On the other hand, we negate it as a concrete manifestation of oppressive power—becoming a mysterious yet sinister cultural symbol in Hollywood films.

To some extent, this intrinsic connection between the pyramid and power is mirrored in our contemporary awareness of megastructure architecture and all large artificial constructs. For a project of sufficient scale and investment, we admire it while simultaneously criticizing and mocking it. However, in the current ideological climate, criticism of the power behind construction is often concealed.

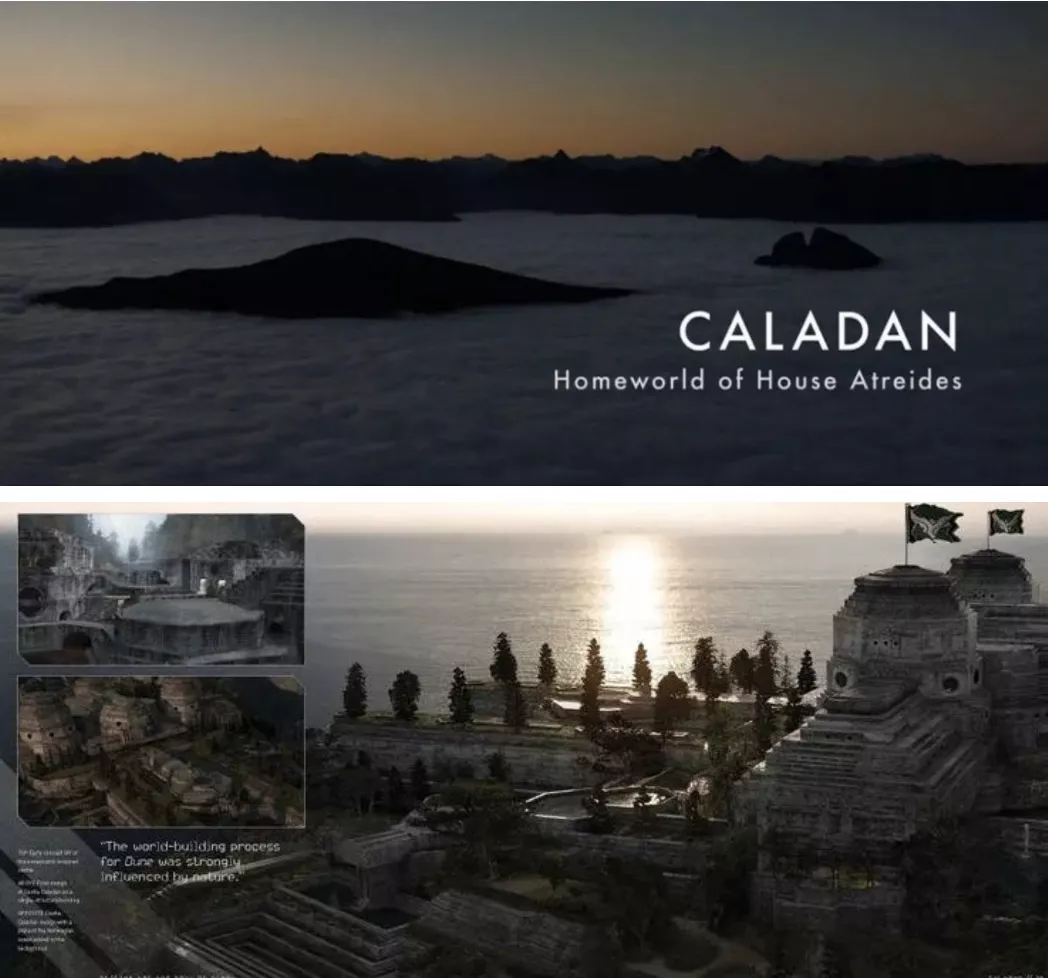

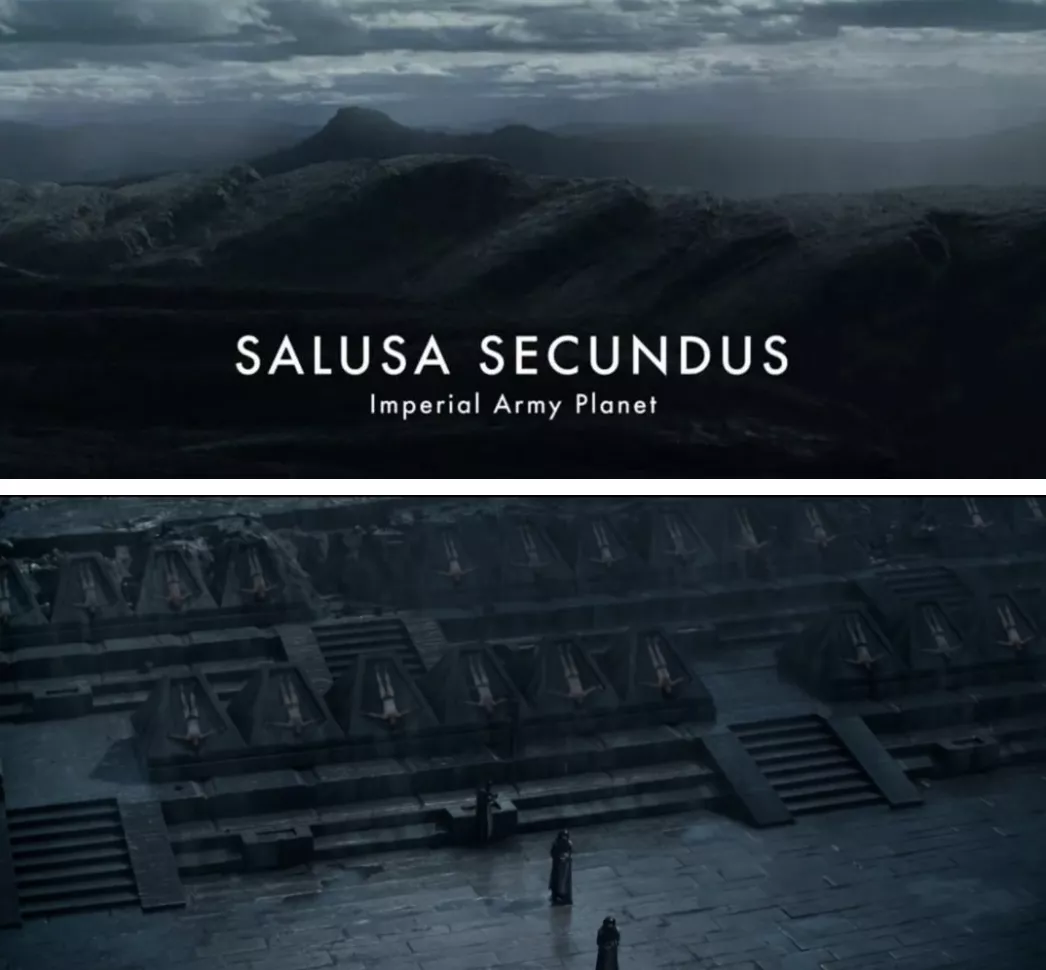

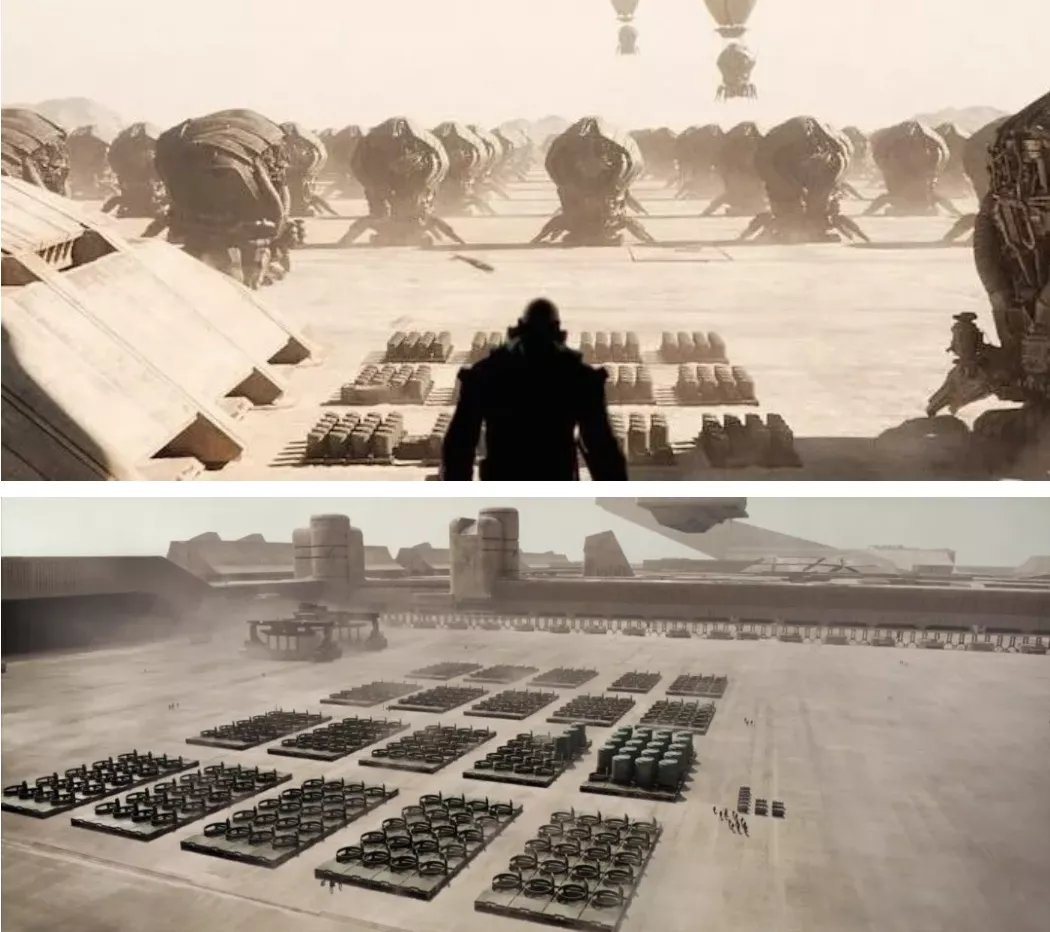

The consciousness of the relationship between megastructures and power is profound. So much so that when faced with a megastructure in a grand scene, it's immediately apparent whether it belongs to the protagonist camp or the antagonist camp. In the "Dune" film, there are four megastructure scenes: the palace of the Atreides family on the planet Caladan, the "Gothic" base of the Harkonnen family, the blood altar of the Emperor's elite Sardaukar troops, and the base castles on the dune planet Arrakis. They all exist in the form of megastructures but carry different attributes of "good" and "evil," regardless of the scene's atmosphere created by audiovisual elements. In other words, purely as spatial objects, why can we identify "just" megastructures and "evil" megastructures through spatial scenes?

Henri Lefebvre argued that space is political, and the production of space is political. When we look at space—beyond the physical space— we're also looking at social space. The object of the judgment of "good" and "evil" of megastructures mentioned above is transferred from our evaluation of a society under a certain power system back to specific material space.

When power becomes a means of action for those who hold it to achieve personal goals, we express disgust, manifested as resistance and negativity, just as the Fremen harbor animosity towards the aliens invading their planet to plunder the spice melange resources. But when power is seen as a collective characteristic, as collective action conducted under the domination of power, such as the organization and construction of the people under the rule of the Atreides family on the planet Caladan, our attitude towards power begins to change. It no longer merely represents coercive oppression and conflicting class contradictions but becomes the essence of human social life. In reality, all human activities and the "great achievements" created by human activities are driven by power. This also explains why we have conflicting feelings toward the pyramid.

Michel Foucault believed that megastructures built under power and domination reveal that all human creativity in social life is both liberating and productive, as well as suppressive and destructive. The phenomenon of power's double-edged sword must be seen as a productive network running through the entire society, rather than merely a negative function of repression.

Our analysis of the double-edged sword phenomenon of power by Michel Foucault does not seek to absolve "evil" megastructures. Similarly, as megastructures, the blood altar of the Emperor's Sardaukar troops and the space of the Harkonnen family base exhibit strong orderliness and axial symmetry in scene composition, emphasizing the unique center on the axis, symbolizing the absolute concentration of power.

In Alejandro Jodorowsky's planned "Dune," visual designer H.R.Giger directly designed the Harkonnen family's base as a giant fortress in the shape of a Harkonnen baron. By symbolizing the pinnacle of centralized power as a "personal monument" within the family, we can speculate that within the building, there must be strict hierarchical spatial conditions with layers of delineation and strict class segregation.

In contrast, the two spaces ruled by the Atreides family, being a feudal principality, also exhibit a hierarchical structure in space. However, observing the construction patterns of their surrounding vassals, they appear to be more free, indicating a certain spontaneity of power under their rule. The architecture blends with nature, and to some extent, the space is open to the public, facilitating interaction and openness.

Another extreme of megastructures is the "underground cities" of the Fremen. In the current storyline of the "Dune" film, the image of the underground city only appears in snippets and in the dreams of the protagonist Paul. However, through some original drawings from various scenes created for "Dune," we can imagine that these cities are carved and built within the natural environment of sand and rock, likely resembling clusters of villages. They are massive in scale but constructed continuously through spontaneous efforts over time. This aligns with the tribal social structure of the Fremen.

Different material spatial structures reflect different social structures. For example, buildings such as castles and palaces at the core of space indicate different class divisions within the social structure. Power unevenly distributes resources among different classes, and the ruling class thus commands vast resources, enabling them to construct megastructures according to their will—creating memorials and symbols far beyond functional needs, such as placing their own busts atop buildings.

Architecture Against Authoritarianism

In the face of such authoritarianism, resistance becomes imperative. "Dune," the film, to me, is not merely a story. When Paul, in a prophetic dream, sees the carnage he unleashes as the messiah Muad'Dib, he weeps bitterly—a warning, perhaps, of the film's profound reflection on power.

How do we wield power without being consumed by it?

How do we, in the future, with technology as depicted in "Dune" and elevated productivity levels, avoid constructing the "evil" megastructures discussed earlier?

Just as we cannot naively suggest abandoning power, nor can we regress to some "good" form of architecture, ignoring technological and productive advancements. Since the Industrial Revolution, the trajectory of architectural development has shown that technological progress is the fundamental force driving architectural evolution: engineers have sometimes contributed more than architects, and inspiration for new buildings has been drawn from automobiles, ships, airplanes, factories, and barns.

In another piece detailing the creation of the film "Dune," we learn that the film's production designer, Patrice Vermette, was influenced by the radical megastructure proposals of Superstudio in his artistic creation of megastructures in the film's scenes. In their famous collage series "The Twelve Ideal Cities," the "thingness" of megastructures is magnified, further reshaping production relations to carry mythical, sacred, and magical values.

The relationship between megastructures and power in the film "Dune" is interpreted step by step as the relationship between creation and creator: humans wield power, and how power is wielded reflects how we reshape the external world to create human civilization. Because power inherently possesses the dialectical properties of creativity and destruction, we need to reflect on power and resist authoritarianism throughout this process continuously. What role does architecture play in this? Architecture serves as a means of transformation and evidence of civilization, but what does it prove?

The imagining of human civilization in "Dune," 10,000 years in the future, maybe fundamentally unrealizable, but the basic relationship remains: different material and spatial structures reflect different social structures. Whether buildings like megastructures serve as relics discovered, examined, and evaluated by other intelligent civilizations after humanity's extinction or are entirely obliterated in the cosmos is uncertain.

The significance of architectural creation lies in the possibility that one's architecture may one day become the last vestige of human civilization, discovered by beings from another corner of the universe: they would not conclude from this that human civilization merely stagnated at a dark level of centralization and class exploitation or capitulated to economic capital's dependency, even losing its ideals.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.