My Secret Christmas Movie:

My Secret Christmas Movie:

Finding Winter Warmth in Agnès Varda’s Kung-fu Master!

December has always been the cruelest month for me. As darkness descends earlier each day and the year draws to a close, I find myself returning again and again to Agnès Varda’s 1987 film Kung-fu Master!. There are no twinkling lights or holiday celebrations in this story of Mary-Jane, a middle-aged single mother played by Jane Birkin, and Julien, a 14-year-old boy lost in the world of arcade games. Yet something about this tender, troubling film speaks to the particular melancholy I feel during these shortest days of the year, when time itself seems to move differently and memories surface like dreams.

Perhaps it begins with the arcade console that stands in front of the supermarket beneath my parents’ apartment, not unlike the one Julien plays throughout the film. In my teenage years, I too fell in love with someone much older, and those pixelated graphics and tinny sound effects now serve as a bridge to both my own past and Varda’s exploration of impossible desire. The game console remains there, still humming with electricity, though the children who once gathered around it have grown up and moved away. Each winter, its glow remains unchanged against the early darkness, while everything else transforms.

What draws me deepest into Kung-fu Master! is its constant examination of vulnerability, particularly through its recurring motif of illness and care. The film is suffused with moments of tending to the sick: Lou’s childhood fever, Julien’s drunken sickness, the specter of AIDS hovering at the edges of the narrative. As Wilson (2021) notes, Varda accomplishes something remarkable here — she shows how maternal tenderness and erotic desire might coexist without destroying each other. These scenes of caretaking become a language of their own, speaking to the ways we reach for connection in our moments of greatest fragility.

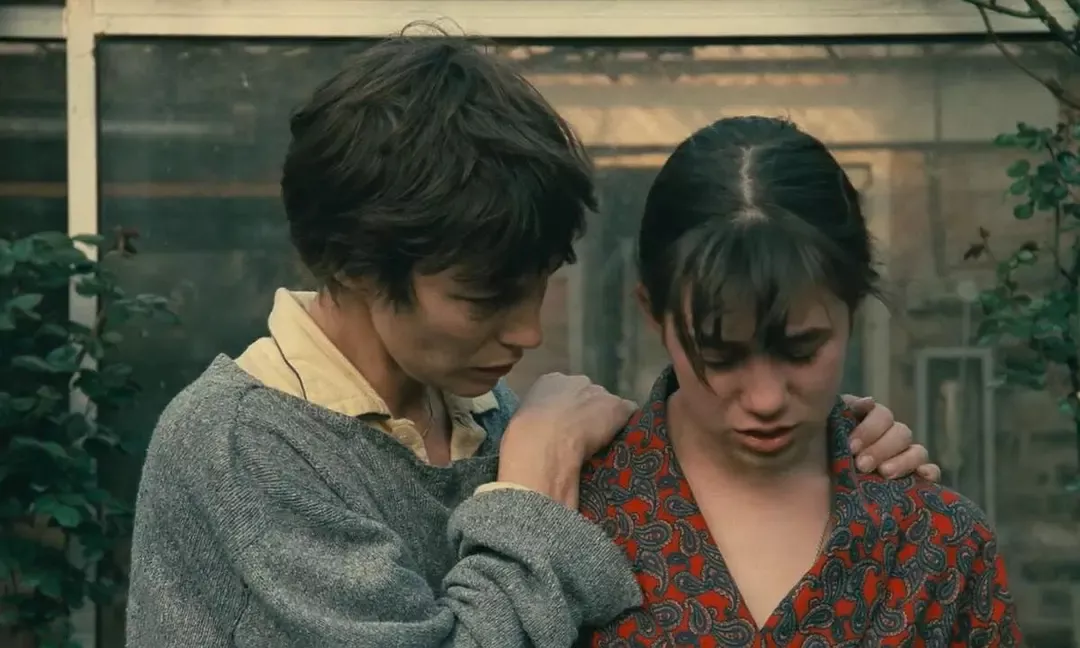

The film’s central sequence haunts me most: Mary-Jane tending to her feverish daughter while Julien watches from the doorway. At first glance, it appears to be a perfect tableau of traditional feminine domesticity — Mary-Jane sitting on the bed, framed by the doorway, singing to her child. The setting itself seems designed to emphasize this domesticity: the iron bedstead, the Victorian furnishings, the floral wallpaper that appears to close in around them. Yet something extraordinary happens in this scene. Through Julien’s presence as an observer, and through Mary-Jane’s awareness of being watched, what begins as an image of maternal confinement transforms into something more complex and liberating. The honeyed light filtering through vintage glass, the Snow White illustrations catching shadows, the soft rustle of Mary-Jane’s paisley shirt — these details no longer simply create an atmosphere of comfortable containment, but suggest the possibility of a fairy tale transformation. When Mary-Jane sings “Ô mon doux fiancé” to her daughter while meeting Julien’s gaze, she breaks through the frame that seems to contain her, creating a moment of startling emotional freedom within the very space meant to confine her. There’s something about the quality of light in this scene that captures perfectly the way the December afternoon sun falls, golden and fleeting, through windows — both illuminating boundaries and suggesting ways to get past them.

What makes these domestic scenes so powerful is how they’re punctuated by moments of escape into the world of video games. In the arcades Julien frequents, time operates differently — measured in lives remaining and levels completed rather than society’s expectations. The games offer a parallel universe where victory, while difficult to achieve, follows clear rules. When Julien teaches Mary-Jane how to play, insisting “No, you gotta keep going for it,” he’s unknowingly articulating a philosophy that will both sustain and complicate their relationship. The game’s rigid structures — its levels, bosses, and princess waiting to be saved — stand in stark contrast to the messy reality of human hearts, yet both share the same truth about desire and persistence.

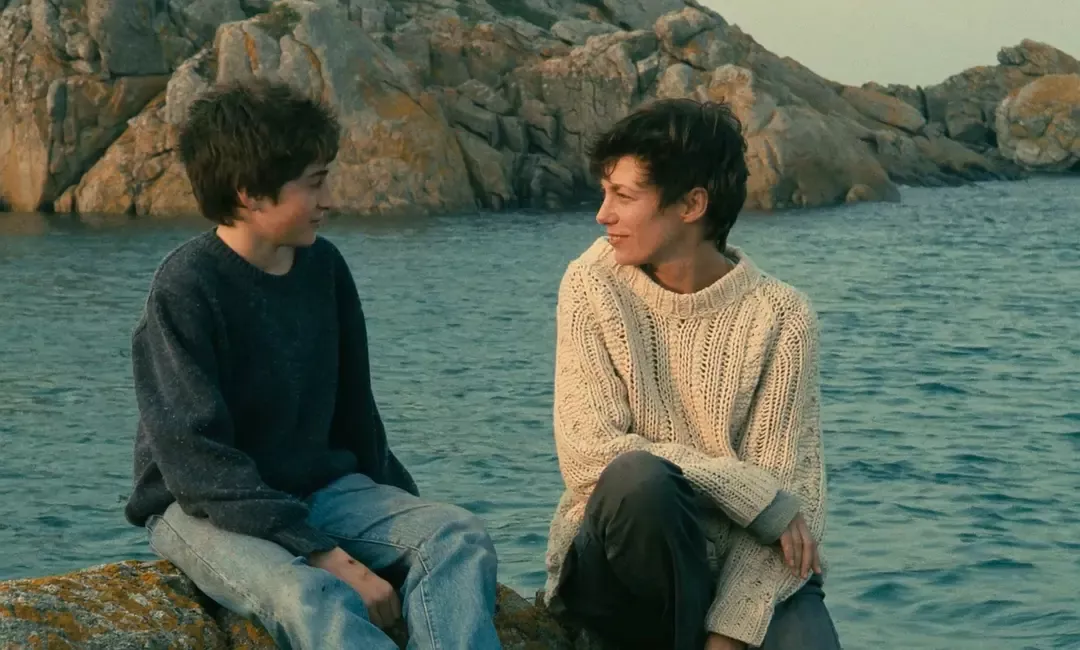

Then comes the island sequence — a fever dream of escape that mirrors my own December fantasies of flight. Mary-Jane, Julien, and Lou flee to a remote seaside paradise, creating their own rituals far from judging eyes. They sleep under stars, forage for eggs, and cry like wild birds. Their makeshift family unit reminds me of the temporary communities that form around arcade machines — brief, intense connections that feel eternal in the moment. But even here, reality seeps in: an AIDS pamphlet becomes a message in a bottle, and Mary-Jane’s quiet admission that she’s “too old” for Julien signals the beginning of the end. Wilson (2021) sees this island as a space where childhood and adulthood blur, where traditional family structures can be reimagined — but only briefly.

The film’s treatment of time particularly resonates during the winter months. Varda captures how certain moments can feel suspended, outside of normal chronology — whether it’s the endless minutes of an arcade game or the timeless quality of caring for someone who’s ill. Yet she never lets us forget that real time continues its relentless motion forward. We see this most powerfully in the scenes after the ‘island fantasy’ ends. Mary-Jane searches empty arcade after empty arcade for Julien’s favorite game, each vacant cabinet a reminder of time’s passage. The gaming consoles, once windows to other worlds, become monuments to what’s been lost.

What makes this film so profound to me is its understanding that some experiences gain their meaning precisely because they cannot last. The fantasy shatters. Reality crashes in. Mary-Jane loses not just Julien but pieces of her relationship with her daughters. Yet the film suggests that these losses don’t negate the beauty or significance of what came before. Like December itself, with its promise of endings and new beginnings, Kung-fu Master! acknowledges both the necessity of change and the worth of what changes leave behind.

Each winter, as others celebrate their holiday traditions, I return to this film like a private ritual. In its quiet observation of human connection and loss, it offers something I need more than seasonal cheer — an acknowledgement of the deep currents of loneliness that run beneath all the celebrations, while still finding moments of unexpected joy. Like the arcade game that gives it its name, it’s about the pursuit of something just out of reach, a quest that feels especially poignant as yet another year slips away. In Varda’s gentle hands, what could have been merely scandalous becomes a mirror reflecting back our most vulnerable selves — those parts of us that ache most acutely in the year’s darkest month.

References

Wilson, E. 2021. Agnès Varda, Jane Birkin, and Kung-fu Master!. Camera Obscura. [Online]. 36(106), pp.41-59. [Accessed 3 December 2024]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-8838529

written by Bonnie

THE DISSIDENTS are a collective of cinephiles dedicated to articulate our perspectives on cinema through writing and other means. We believe that the assessments of films should be determined by individuals instead of academic institutions. We prioritize powerful statements over impartial viewpoints, and the responsibility to criticize over the right to praise. We do not acknowledge the hierarchy between appreciators and creators or between enthusiasts and insiders. We must define and defend our own cinema. |

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.