Set in 1987 Romania, on a cold day after the snow has melted, the story unfolds within a single day. Ottila, a college student, buys smuggled cigarettes, food, and soap from a black-market seller in her dormitory building to secretly prepare for her roommate Gabita, who is pregnant. Abortion is illegal in Romania at that time, so they seek out a man named Mr. Bebe to perform the procedure privately. What follows is a nightmare. In a cheap hotel, Mr. Bebe not only demands money but also coerces Ottila into complying with his sexual advances. Ottila reluctantly agrees and helps Gabita dispose of the fetus, throwing it into a trash bin. After the fear and unease subside, the two girls sit silently in the hotel restaurant, waiting for their dinner. In the distance, a lively wedding celebration is taking place. This day marks exactly 4 months, 3 weeks, and 2 days of Gabita's pregnancy.

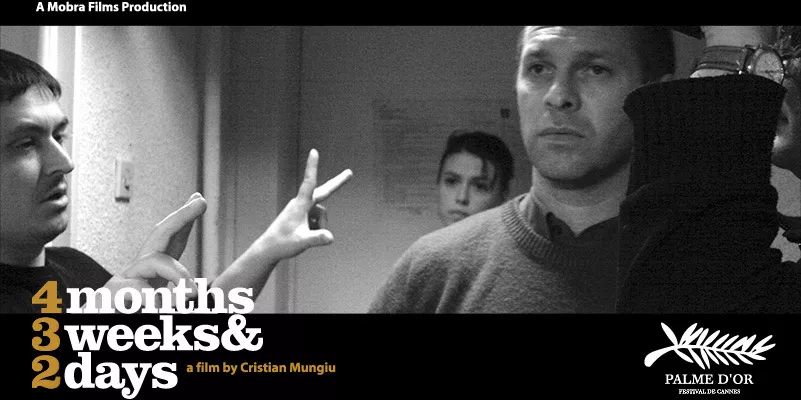

While the plot may seem mundane on the surface, this film is exceptional. If you can endure the immense tension portrayed throughout the two-hour duration, you will understand why Cristian Mungiu, the 39-year-old director, writer, and producer of this film, won the Palme d'Or at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival.

At the Outside

According to director Cristian Mungiu, this film explores themes of friendship, responsibility, and love, rooted in experiences and secrets that are often too difficult to share with others. At its core, it tells the story of an abortion. In 1966, the Ceausescu government in Romania implemented a law prohibiting abortion, which remained in effect until 1989 when Ceausescu's regime ended, and the law was repealed. During this period, approximately 500,000 Romanian women died due to unsafe clandestine abortions, often in shame. Abortion was not only considered morally wrong and sinful but also a betrayal and defiance of the state system.

Set in 1987, on the eve of political upheaval in Eastern Europe, the film is sometimes viewed by Western commentators and viewers through a lens of political oppression and metaphors. However, I believe more in the director's intentions, which he made very clear in his director's statement:

"I tried to make a film about characters and stories, not about that era. That's not the context or theme of the film. I tried to respect and restore the facts as much as possible, rather than focusing on the clichés and symbols of the late communist era. That era is there, in my film, but it's behind the camera: the noisy exhaust emissions of buses, Romanian cars shaped like irons, poor suitcases, walls covered with books, and some habits of people at that time, such as Kent cigarettes being used as currency in private circulation. Without these background elements, we wouldn't be able to understand this film.”

In the Inside

In contrast to the weak and somewhat selfish Gabita, Ottila embodies strength and bravery. She acts as a guardian angel to Gabita, handling various challenging situations despite feeling helpless and scared herself. After being violated by Mr. Bebe, Gabita rushes into the bathroom and vigorously scrubs her body, then sits motionless in the bathtub, her back to the camera, her expression invisible but conveying immense anguish. On the bus leaving the hotel for her boyfriend's house, Ottila silently sheds tears from a distance in the frame. She harbors some resentment towards Gabita, partly due to Mr. Bebe's threats and Gabita's careless lies. However, this resentment quickly turns into concern because she is the only one who can help Gabita. This is exemplified by Ottila leaving the last cigarette for Gabita.

A pivotal moment in the film involves a close-up shot of the fetus's body after an abortion. The 4-month-old fetus is depicted vividly and realistically, wrapped in a white bath towel, hand-sized, faintly humanoid, and covered in bloodstains. Ottila puts the fetus in a book bag and rushes out of the hotel. The camera follows her through dark alleys, capturing only her shadowy figure moving in the darkness and the sound of her hurried, suppressed panting out of fear and nervousness. Eventually, she finds an apartment building and hastily disposes of the fetus's body in a trash can in the hallway. In the dim light, her silhouette stands quietly in front of the trash can.

The film is replete with suspenseful moments that create an immersive, tense, and shocking atmosphere. Viewers can almost hear Ottila and Gabita's breaths and heartbeats. Mr. Bebe's assault on Gabita is captured from outside the room as she anxiously waits, unaware of what is happening inside. Gabita is left alone in the hotel, while Ottila, who rushed to her boyfriend's mother's birthday party, is restless and repeatedly calls Gabita, only to be interrupted by unexpected events. Even when they do connect, there is no answer. The film's somber tone and Gabita's fragile image seem to foreshadow a tragedy. Like Ottila rushing to the train station, viewers are filled with anxiety, and relief washes over them at the last minute upon seeing that Gabita is still alive.

The film's cinematography and performances are also noteworthy. Cristian Mungiu opted for a dark tone and avoided scenes that appeared too orchestrated. To achieve authenticity, he employed extreme techniques such as excessively long takes—essentially one shot per scene—handheld shooting without steadicams, tripods, or intentional movement, and an abundance of voice-overs, with characters often speaking off-camera. These elements serve to bring forth the film's original soul: emotion and truth.

Anamaria Marinca's portrayal of Ottila was incredibly impressive. She was a relatively unknown Romanian actor trying to make it in London before being cast. Director Cristian Mungiu didn't find the actress for Ottila until a week before filming. He flew to London with an open mind to meet Anamaria. In his director's statement, he wrote: "When I first met her at the airport at night, I was disappointed because she didn't look like Ottila at all. But the next day, during the audition, something unbelievable happened. She completely became Ottila. I saw my character coming alive through her lips. She was so unforgettable that the whole movie could be said to have been carried on her shoulders. If there's one thing that makes me feel perfect about this movie, it's the acting." Just like Anamaria Marinca's performance, I firmly believe that every good actor possesses incredible energy and a certain neuroticism that ordinary people don't possess. When the camera rolls, they embody perfect lies, presenting another version of themselves to the world.

Great movies are pure and complete; they make you forget the presence of the director or camera, and you also don't feel any individual actors. They provide a deeper understanding of the world behind appearances, moving us or evoking small moments of happiness and sadness, leaving us speechless for a long time.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.