While art cinema finds its quintessence more in Europe, its emulation elsewhere still needs to be discovered. Faced with the looming impact of Hollywood's commercial mainstream, European governments, back in the 1970s, began sensing a deep threat. They realized that European cinema stood on the brink of either extinction or complete Americanization. Consequently, they initiated policies involving government funding and tax incentives to safeguard indigenous films and their associated cultural values, forming a counterbalance to Hollywood. The poignant historical narrative of a prolonged struggle led to a shared understanding: survival for local filmmakers was untenable without governmental support. As a result, France subjected receipts from American films to heavy taxes to subsidize domestic productions, while German filmmakers leveraged tax evasion laws to secure significant financing through media funds. The survival of European art cinema owes itself entirely to governmental protection.

Film critics and scholars perceive art cinema as possessing "formal characteristics distinct from Hollywood mainstream films." These characteristics usually manifest as a consciousness of social realism, emphasizing the director's authorial expression, focusing on the characters' thoughts, dreams, or motivations rather than explicitly laying out the story. Film scholar David Bordwell further asserts that art cinema is "a film genre with its unique conventions."

In 2021, a recent Toronto International Film Festival compilation showcased 30 non-Hollywood films made between 1946 and 1973, a significantly higher proportion compared to other periods in a list of the top 100 films. Moreover, among its top 25, 12, precisely half, hailed from that era. This list aptly encapsulates the question of "for whom is art meant" in cinema.

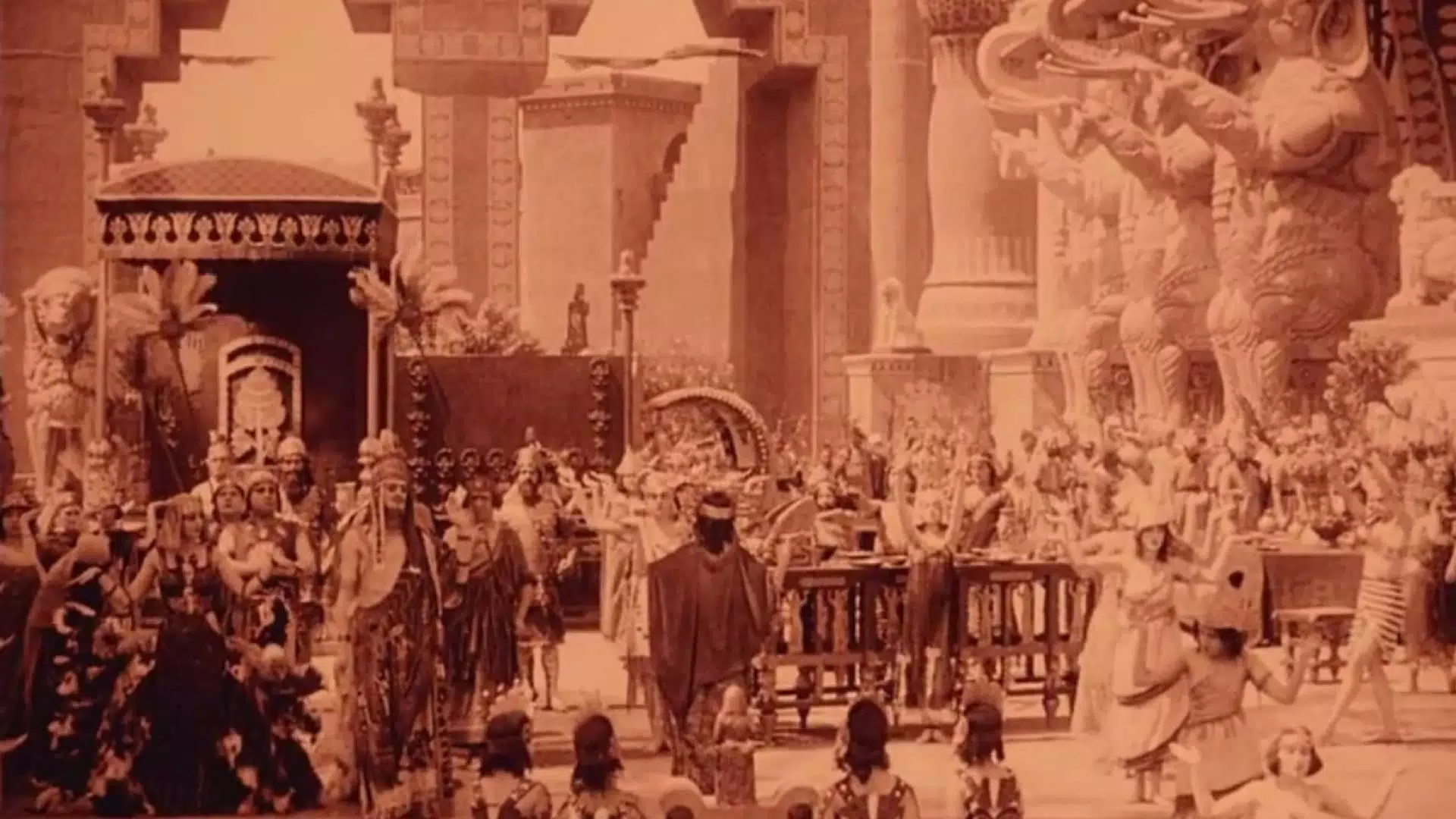

Interestingly, the genesis of art cinema originated somewhere other than Europe. "Intolerance," directed by David Griffith in 1916, is academically recognized as the first-ever art film. It was followed by Sergei M. Eisenstein's "Battleship Potemkin" in 1925, nearly a decade later. The enduring influence of these two filmmakers led to diverse art film movements across various European countries in the subsequent decades. Even as early as the 1920s, European filmmakers collectively differentiated between entertainment and art, categorizing films into two types: entertainment films for the masses and serious art films for knowledgeable audiences. This led to the emergence of various movements and schools of thought, originating primarily from Spain, France, Italy, and Germany, among others, including avant-garde movies, cinéma pur, absolute films, abstract films, futurism, neorealism, and The French New Wave, among others.

The transatlantic interaction resulted in Hollywood films from the 1930s, divided into artful adaptations of literary works and mass-appeal genre films. By the end of World War II, more audiences became aware of the distinction between European films, represented by Italian neorealism, and Hollywood mainstream cinema, giving rise to the development of art cinemas limited mainly to metropolitan and university towns. This awareness, reinforced by art cinemas, led to an increasing number of mainstream audiences growing weary of blockbuster commercial films and turning towards art cinemas for an alternative viewing experience. Comparatively, our industry development has yet to reach Hollywood's stage in the 1940s. The so-called art films still need the foundation to break away from mainstream commercial films: the missing link lies in content creation and audience development. At that time, the success of American mainstream films stemmed from a rich tapestry of British films, foreign language films, and American independent films, along with underground experimental films, documentaries, short films, and revivals of Hollywood classics. However, due to restrictions in import quotas and censorship systems, we're still trying to match this abundant source of films and support an art cinema chain, making it difficult for even a single art cinema to survive.

Any so-called "art film" that earns a place in cinematic history must reflect societal, humanistic, and existential revelations. It must be sharp-edged, unconventional, diverging from mainstream norms, and challenging mainstream values. Its narrative impetus must adhere to the realism of the director's expression, employing fragmented and loose storytelling structures and an artistic style emphasizing inner conflicts. Its characters often embody confusion, abnormality, or even deviance. They express extensive dialogues (sometimes monologues) to articulate thoughts and construct emotions through slow-paced, long shots. They assertively raise questions (especially about human nature's and life's dilemmas) and explore problems passionately. However, they intentionally refuse to provide a logical, definitive resolution, deliberately leaving the audience disoriented: why is it so? Why does the story unfold in this manner? Therefore, art films rely on a niche fan base built upon high-end intellectual promotion and word-of-mouth advertising to survive. These so-called art films are not escapist or purely for entertainment but rather an intellectually stimulating experience appreciated only by a select few. Due to their niche nature, sustainability requires a low-cost model.

So, who exactly is art cinema meant for? In Europe, it's art meant for the government—a way to subsidize and nourish these so-called "cultural exceptions" using taxpayers' money. However, American filmmakers aren't as fortunate; they must rely on the audience to survive. Thus, its developmental trajectory can never diverge from the audience.

This is because that era concentrated on three generations of filmmakers and their devotees (veterans of World War II, those who grew up in the 1960s, and those born post-war up to the 1960s). The fusion of these three generations spurred the prosperity of world art cinema in the United States, a fortunate minority. They preferred more profound films—for instance, World War II veterans who once served overseas, possessed an international perspective, and, upon returning home, availed themselves of free education due to the prevailing post-war veterans' welfare legislation. They were more informed about non-American cultures and, thus, more interested in foreign art films and non-Hollywood independent films. The lucky few were also called the "Golden Age" generation—those born in the late 1920s and early 1940s who managed to dodge the war. They relished the post-war boom and the explosion of artistic expressions afterward. America's renowned film critics emerged from this generation: John Simon, born in 1925; Andrew Sarris, born in 1928; Richard Roud, born in 1929; Eugene Archer, born in 1931; Susan Sontag; Richard Schickel, born in 1933, and Molly Haskell, born in 1939. When the wave of foreign films surged, they were at the most perceptively acute age of their twenties and thirties.

Also, late bloomers like Pauline Kael, born in 1919, joined the ranks in the 1950s alongside Sarris. These critics' professional deciphering completed the food chain, enabling the survival of art cinema and establishing a triangular loop between the author, the text, and the reader. By the 1960s, the baby boomer generation, born post-World War II, also jumped onto the art film bandwagon, substantially contributing to its momentum.

The support from these audiences made 1946 to 1973 the golden age of the American art film market. Intellectual magazines such as "Film Comment" and "Film Culture" enhanced imported films' urban allure. Within a few years, ambitious entrepreneurs started marketing British comedies, Swedish psychoanalytical dramas, and movies featuring Brigitte Bardot, eventually leading to The French New Wave and the young films of the 1960s. Distributors endured hardships to bring these foreign films to theaters in Manhattan's East Side, and audiences flocked in. These "foreign films" (often re-edited, sometimes re-dubbed, or with English subtitles added), were marketed with "shocking," "heartwarming," or even "erotic" tags to appeal to the growing tastes of urban and university youth.

This commercial operation, borne of cinematic passion, was crucial for the survival of art cinema. For instance, at that time, Akira Kurosawa was less famous due to a lack of meticulous packaging, whereas Ingmar Bergman became a fashionable sensation. He even graced the cover of "Time" in 1960 and won consecutive Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film ("The Virgin Spring" and "Through a Glass Darkly"). Eventually, these foreign directors caught the attention of major Hollywood studios. Since small distributors proved that these niche "circle films" were profitable, large companies began embracing imported films, first by distribution, then by direct investment. For example, Columbia Pictures invested in films like "A Married Woman" and “Masculin Féminin”. This clearly illustrates that art does not separate from money, and money does not abandon art. With adequate respect for money, it's evident that these foreign films and Hollywood, art, and commerce are not irreconcilable; from the start, their relationship has been ambiguous: even the most artistic film relies on an economic system for production, packaging, and circulation. The relationship between commercial cinema and personal films, commerce, and art isn't fixed but somewhat fluctuating. After all, Rembrandt also painted commercial works, and Mozart's "The Magic Flute" was originally a commissioned piece. Sometimes, good art is good business.

Share your thoughts!

Be the first to start the conversation.