Argentine filmmaker, screenwriter, and producer Lucrecia Martel is, as a general consensus, not your run-of the-mill artist; or human, really. A bona-fide Sagittarius, she enjoys cigars, cat's-eye-glasses, rarely repeats herself, is not an "industry director" by any means, and, according to The Believer magazine, apparently has a 'cult following' of which she is totally unaware. With a vast and wide array of productions, her work is frequently produced by legendary Spanish filmmaker Almodóvar.

Despite a solid academic background, Martel considers herself mostly an autodidact, and indeed, British Film Institute theorists have been known to call her practice and visions "idiosyncratic, quite brilliant, filmmaking in her own time and by her own rules"; while Vogue magazine went as far as claiming in a retrospective that was done on her her when her Zama was released in 2017 that "If she was American, she'd probably be famous."

Well, then. For now, this eccentric figure lives in Buenos Aires with her wife Julieta, and despite any recognition, underground or otherwise, she may have been getting along the way, to me, Martel is like an Olympic boxer of cinema. She'll right-hook her opinions at you while throwing in some left-jabs all in one go in different layers, and while this is all up for the viewer to perceive, it all goes back to her roots and identity.

To IndieWire, Martel was once quoted as saying: "My love of storytelling comes from oral tradition, the stories from my grandmother and conversations with [my] mother. The world is full of discussions of condensation, drifts, misunderstanding, repetition. These are the materials I work with. My debt is to these women."

This part of her becomes the starting point from which to widen all the discussions she wants to expand on, ever so subtly, ever so jarringly, ever so transgressively.

As examples of what I'm trying to convey, I'll touch upon two of her most acclaimed and awarded works; The Swamp (La ciénaga, 2001), and The Headless Woman (La mujer sin cabeza, 2008).

La ciénaga (The Swamp, 2001) is Martel’s first feature film, and was shot in her home province of Salta, in northern Argentina. It is the tale of a bourgeois family who cannot accept that their way of life is no longer financially feasible. The house is in various states of decay, which is reflected in the murky looking pool that serves as one of the main locations for the film. As the adults of the story drink and hang out around it, the children fill in and assume the grown-up roles. The main event is the dynamics of the relationships between people, which alternate between highlighting their untraditional, sometimes destructive, and comprehensively dysfunctional behavior/feelings towards one another; and the entire family’s isolation, in that the only non-family members they socialize with are indigenous servants.

La ciénaga deals with religion, comments on racial/class tensions, and criticizes the extremely conservative Argentine bourgeoisie, the treatment of indigenous people, and machismo.

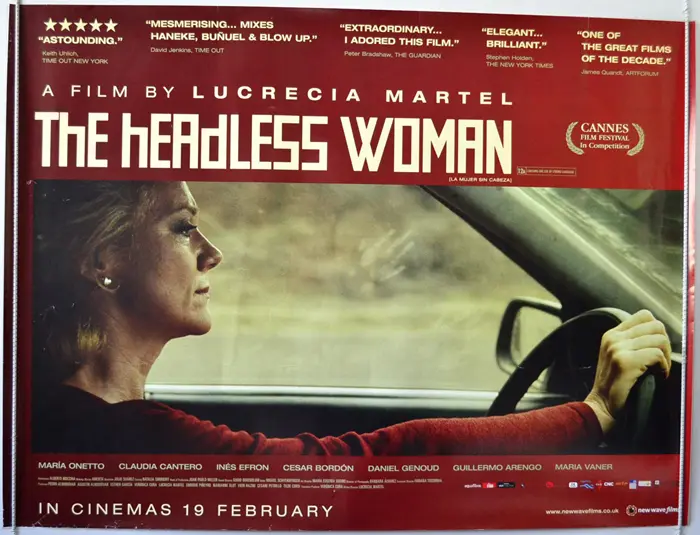

La mujer sin cabeza (The Headless Woman, 2008) is Martel’s third feature film, also shot in Salta. It’s the story of Verónica, a well-to-do dentist who starts to unravel mentally and emotionally after leaving the scene of a hit-and-run in which she doesn’t know whether she had killed a dog or an indigenous boy. Throughout the film, her state deteriorates quickly, as everything from her husband’s dead game to her patients at the practice seems to taunt her. When she cracks and tells her husband, he proceeds to enlist the help of connections with the police, doctors, and news people to cover the whole thing up. In the end, we the audience are almost as unsure as Verónica as to what, in fact, happened. In this film Martel paints again a picture of the contrast between the world of the ‘haves’, again represented by the large aristocratic family, and that of the ‘have nots’, the indigenous characters who are only there to serve the first group in some way.

The idea of social segregation is explored again, though differently from in La ciénaga in that it focuses on the power of the aristocracy, based largely on their complicity with the military regime. Verónica is the embodiment of the idea of a soulless body, a representation of Argentina without its history. A country with no history has no identity, and therefore, no clear future. An idea which is visually represented constantly by the fact that seldom does she ever appear without some part of her cut off the frame (see how headlesss she is?)...

So then this is how this cinematic boxer opens up her multipurpose fan of criticism aimed at, well, pretty much everyone. As mentioned before, but in short: in-your-face main themes include racial and class tensions, and segregation, and vehement criticism of Argentine bourgeoisie and commentary on modern systemic divisions. She also criticizes the treatment of South American indigenous people, attacks machismo as a culture (and as such, a behavior that women too can reproduce), and makes a mockery of religion.

Some of the denoting elements/characteristics of her work are the depiction of large, dysfunctional aristocratic families, and some sort of homosexual platonic crushes. Apparently, she also doesn’t necessarily denounce incest, so relationships between family members have been observed to get a little... peculiar, shall we say?

In fact, both films are largely characterized by the direction of child actors, who assume various different roles, but invariably call attention to the chaos of these large clans. She then creates what are called “fish tank spaces”, where all kinds of relatives are made to coexist in invariably cramped and small environments. Narratively speaking, not much happens in terms of action, but almost everything is said in the dynamics between characters.

Furthermore, sound is paramount in not only enhancing, but creating narrative events, sometimes even off-screen, as is the case with many sequences in La mujer sin cabeza. These instances in the film, in addition to the choice of the cinemascope to distort the edges of the frame and the focal character’s features at the same time give the film an eerie and unhinged sort of perspective/aspect.

Though Martel doesn’t get the recognition she deserves in the United States (i.e., Hollywood and the mainstream world at large- and I, for one, as a fellow Sagittarius and fellow filmmaker would imagine she doesn't even care about that), she has a staggeringly long list of awards and nominations under her belt and is widely celebrated both internationally and in South America.

Often winning or participating in multiple categories in a single festival, many of her winnings have come from La mujer sin cabeza and La ciénaga. Some festivals she’s won include Rotterdam, Sundance and Berlin International Film Festival, while nominations include Cannes, Berlin and Chicago International Film Festival. And if you didn't know about her, now you do.

*Pause for standing ovation.*

Log in

Log in

No comments yet,

be the first one to comment!